Frontier Craftsmanship, Arctic Innovation

"In the Last Frontier, makers transform raw materials into treasures—salmon into smoked delicacies, native metals into jewelry, and wilderness into wearable art."

Where the Wild Meets the Workbench

Alaska's manufacturing tradition is written in ice, carved from wilderness, and tempered by the elements. From the salmon-rich waters of the Bering Sea to the gold-laden creeks of the Interior, this vast state nurtures artisans who work with the land's bounty. Here, smokehouses in remote villages produce world-renowned salmon, goldsmiths in Fairbanks create heirloom jewelry from Alaska's mineral wealth, and Eskimo artisans transform baleen into works of art. Each brand featured here embodies Alaska's frontier spirit: resourcefulness born from isolation, quality necessitated by the climate, and a deep respect for the state's natural heritage. In Alaska, every object is crafted with the understanding that it must last—for winter is long, and supplies are far away.

Silver Gulch Brewing & Bottling

"Craft brewery producing 'Alaska's Best Beer' with pristine glacial water and local ingredients."

A Family Legacy

In 1998, two Fairbanks friends—John and Rob—had a radical idea: prove that world-class beer could be brewed in Alaska's harsh Interior climate.

With $2 million in startup capital and a commitment to never using water filtration (they draw from 300-foot-deep artesian wells that produce water so pure it needs no treatment), Silver Gulch has become Alaska's largest brewery.

The company's philosophy is simple: 'Respect the ingredients, respect the process, respect the people who drink our beer.' Their 'Silver Gulch Gold'—a dry-hopped pale ale with a citrusy bite—was born from experiments with homegrown hops, proving that Alaska's 20-hour summer days could produce extraordinary brewing ingredients.

Beyond beer, they've created a vertically integrated tourism destination: brewery tours, a restaurant serving locally-sourced game (moose, caribou, salmon), and a retail shop selling everything from flannel shirts to artisanal sodas.

The success of Silver Gulch has inspired a generation of Alaska entrepreneurs, proving that manufacturing in the Last Frontier isn't just possible—it's profitable.

The Art of Handcrafted Excellence

The heart of Silver Gulch's production is its 70-barrel brewing system, custom-built in Germany and installed in a 50,000-square-foot facility in Fairbanks.

The brewing process begins with that unique glacial water, drawn from deep aquifers beneath the brewery.

Hops—sourced from both Pacific Northwest farms and their own experimental plot—are added at precise intervals to create the signature bitterness and aroma.

The fermentation process uses house-cultured yeast, stored in a temperature-controlled 'yeast lab' that ensures consistency across batches.

What truly sets Silver Gulch apart is its 'Cold Conditioning' process: unlike most breweries that filter to remove yeast, Silver Gulch ages its ales in cold storage at 34°F for weeks, allowing natural settling and the development of complex flavors.

The bottling line, capable of filling 500 bottles per minute, is among the most modern in the Pacific Northwest, yet they still perform 'hands-on' quality checks at critical points.

The beer is packaged in a distinctive silver can design that reflects Fairbanks' nickname as 'The Golden Heart of Alaska.'.

Bessie Moos Honey

"Pure Alaskan wildflower honey from bees foraging in Denali National Park region."

Innovation Born from Necessity

When Bessie Moos passed away in 1997, she left behind a unique legacy: a thriving honey operation in Healy, Alaska, operated by her daughter and son-in-law.

Most people assume honey production is impossible in Alaska's subarctic climate, but Bessie proved them wrong.

Her secret was a hybrid breed of bees—Russian Carniolans and Italian hybrids—carefully selected for cold-hardiness and resistance to harsh winters.

These bees forage on wildflowers that bloom in Alaska's brief but intense summer, producing honey with a distinct flavor profile found nowhere else on Earth.

The honey has notes of wild blueberry, fireweed, and boreal forest plants, creating a taste that captures Alaska's wilderness in a jar.

Bessie's grandson, who now runs the operation, maintains the original principles: no artificial feeding, no chemical treatments, and complete respect for the bees' natural cycles.

During the 20-hour summer days, the bees work nearly around the clock, producing honey with an intensity that can't be replicated elsewhere.

The honey is so pure that it doesn't crystallize for months, and when it does, it forms a smooth, spreadable texture that many prefer to liquid honey.

The Art of Handcrafted Excellence

The honey-making process at Bessie Moos is entirely weather-dependent and follows the rhythm of Alaska's extreme seasons.

In March, the hives are checked for winter survival—a critical moment when many operations fail.

The bees are fed a proprietary mixture of their own honey and natural supplements if needed.

As the snow melts in May, the hives are moved to 'bee yards' near Healy, where wildflowers begin to emerge.

The critical window is the 10-week period from June to August when the bees collect nectar from fireweed (Alaska's state flower), wild blueberry, raspberry, and willow catkins.

The extraction process happens in a temperature-controlled room where honey is spun from the combs using centrifugal force—a technique that preserves the honey's enzymes and flavor compounds.

Each batch is tested for moisture content (ideal: 17.5-18.5%) to prevent fermentation.

The honey is never heated above natural hive temperatures (95-98°F), ensuring it remains 'raw' and unprocessed.

After extraction, the honey rests in settling tanks for 72 hours, allowing air bubbles and wax particles to rise to the top.

It's then bottled by hand in distinctive bear-proof jars—a necessity in bear country—and labeled with harvest dates and flower sources.

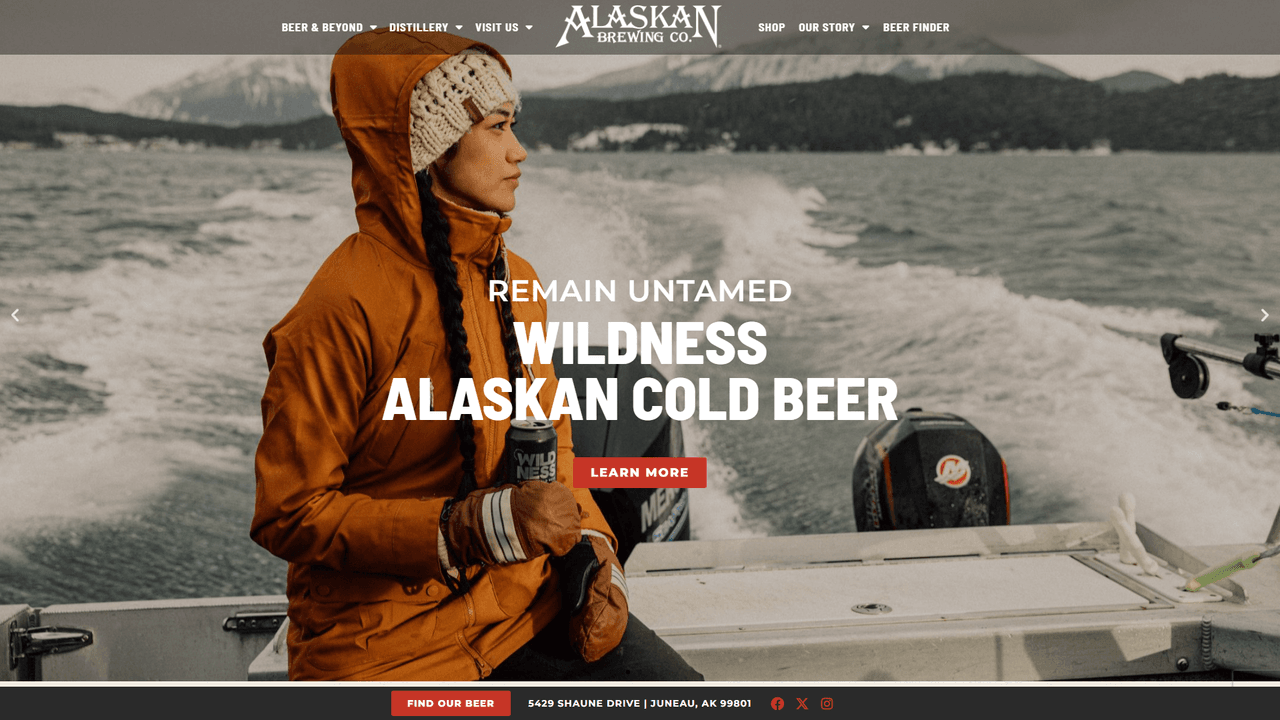

Alaskan Brewing Co.

"Pioneer Alaskan craft brewery famous for Smoked Porter with locally foraged alder wood."

A Living Tradition

In 1986, Geoff and Cindy Larson had a vision: create a beer that tasted like Alaska.

Their solution was to use alder—the same wood that Native Alaskans had used for smoking salmon for centuries—to smoke malt in the brewing process.

The result was Alaskan Smoked Porter, a beer unlike anything produced elsewhere.

But building a brewery in Juneau came with unique challenges.

The town is only accessible by boat or plane, every ingredient must be shipped in, and the brewery occupies a former salmon cannery.

The Larsons persevered, driven by a commitment to using Alaskan ingredients and traditional brewing methods.

Today, Alaskan Brewing Co.

operates out of a 40,000-square-foot facility that produces 85,000 barrels annually.

Their innovation didn't stop with smoked porter; they pioneered the use of glacier water in brewing, developed unique yeast strains that thrive in cold conditions, and created the 'Glacier Brewhouse'—a tourist destination that draws visitors from around the world.

Their 'Alaskan Amber' became the first beer to bear the 'Made in Alaska' seal, and their success proved that craft brewing could not only survive but thrive in the remote Last Frontier.

Innovation Meets Craftsmanship

The heart of Alaskan Brewing's production is its signature Smoked Porter, a process that begins in the malt house.

Alaskan is one of only six breweries in the world that malts its own grain, a technique that allows precise control over the smoking process.

Local alder wood is burned in a custom smoker, creating smoke that circulates through the malt at controlled temperatures.

The smoked malt contributes 30-40% of the base grain bill, infusing the beer with a complex smokiness reminiscent of campfire and salmon smokehouses.

The brewing process uses glacier-fed water filtered through volcanic rock, providing water with a mineral profile ideal for beer.

Fermentation occurs at cooler temperatures (58-62°F) than typical ales, allowing the unique yeast strains to develop flavors impossible to replicate in warmer climates.

The beer is aged for 6-8 weeks in cold conditioning tanks, developing the smooth, chocolate-like character that has made it famous.

Packaging happens in a state-of-the-art facility where cans are filled with nitrogen-sparging to prevent oxidation.

Every batch is tasted by the brewers before release—maintaining the 'taste it like an Alaskan' standard established in 1986.

Raven Sculptures

"Hand-carved totem poles and sculptures by Tlingit artist preserving indigenous craft traditions."

A Living Tradition

In Sitka, the heart of Alaska's indigenous culture, master carver Nathan Jackson continues a tradition passed down through generations.

Jackson, a Tlingit artist born into a family of totem pole carvers, learned the sacred art of wood carving as a child, watching his father and uncles transform massive cedar logs into towering expressions of family history and tribal lore.

For the Tlingit, ravens are not merely birds—they are tricksters, creators, and cultural heroes.

Jackson's sculptures capture this complexity, depicting ravens in动态 poses that tell stories of the sky, the sea, and the spirit world.

What began as personal commissions for local Tlingit families has evolved into an internationally recognized studio.

Jackson's works can be found in museums from Alaska to Europe, yet he remains committed to teaching young artists and preserving traditional techniques.

Each sculpture is carved from red or yellow cedar, wood selected not just for its beauty but for its spiritual significance to the Tlingit people.

The studio operates as both a workshop and a classroom, where apprentices learn not just the technical aspects of carving but the cultural stories embedded in each design.

The Art of Handcrafted Excellence

The carving process at Raven Sculptures begins with selecting the right cedar—often logs that have been felled by storms or windthrow, a practice that honors the tree's spirit.

The wood is split using traditional techniques, then roughed out using chainsaws before the detailed work begins with hand tools.

Jackson uses gouges and chisels passed down from his father, tools that have been in the family for three generations.

Each piece of the sculpture is carved to tell a specific story; the raven's beak might represent the trickster's cunning, its raised wing the spirit of flight and freedom.

Traditional pigments made from natural materials—charcoal, ochre, and berry juices—are applied using brushes made from animal hair.

The studio uses a custom drying process: sculptures are aged for months in a temperature-controlled environment, allowing the wood to settle and the carvings to stabilize.

Before a sculpture leaves the studio, it's blessed using traditional Tlingit ceremonies, a practice that acknowledges the life of the tree and asks permission for the story to be told.

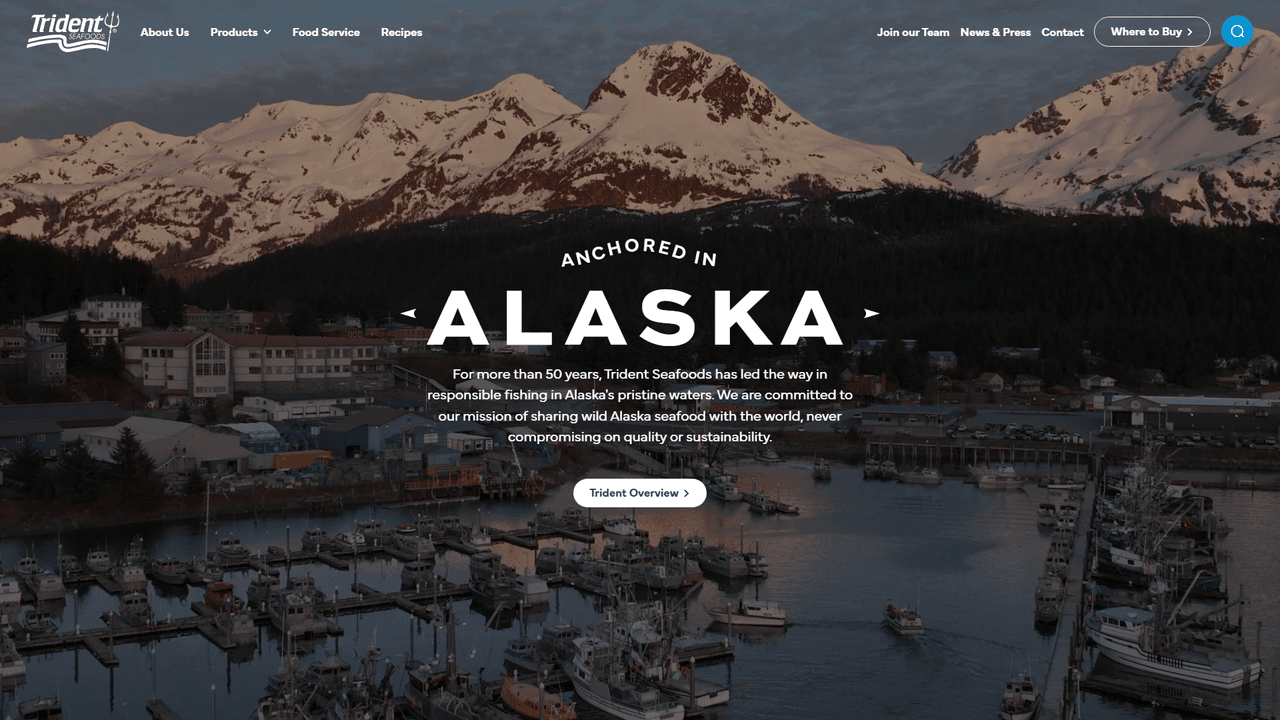

Trident Seafoods

"Processing wild-caught Alaskan salmon, pollock, and crab using traditional smoking and canning methods."

The Story Behind the Brand

In 1968, three Alaskan fishermen—frustrated with middlemen who took most of the profit from their catch—decided to take control of their destiny.

They formed Trident Seafoods with a simple philosophy: 'Respect the fish, respect the fishermen.' What began as a small operation in Seattle has grown into one of the largest seafood processing companies in the world, but its heart remains in Alaska.

Trident operates 12 processing facilities throughout the Aleutian Islands and Bering Sea, bringing world-class seafood to global markets while maintaining the quality standards that Alaskan fishermen are known for.

The company's 'wild-caught, never farmed' commitment ensures that every salmon, pollock, and crab product reflects the pristine waters of Alaska.

Their smoked salmon process—derived from Native Alaskan techniques—produces delicacies that have become favorites in high-end restaurants from Tokyo to New York.

Trident's success has allowed them to invest in sustainability initiatives, including the 'Trident Resource Restoration' program that funds habitat restoration projects throughout Alaska.

Time-Honored Techniques

Trident's processing facilities operate on a 'from boat to box' principle, with processing beginning within hours of the catch.

Salmon are immediately bled and gutted on board the fishing vessels, then rapidly cooled in refrigerated seawater to maintain peak freshness.

At the Akutan facility, salmon are filleted using automated systems that ensure precise cuts while preserving the fish's natural texture.

The fillets are then brined in a solution of salt and Alaska's pristine glacial water before being smoked over alder wood—a process that can take 12-24 hours depending on the desired flavor intensity.

Trident's canning process follows the traditional method: fish is packed in cans with minimal processing, sealed, and cooked in retort ovens that reach temperatures of 240°F.

This 'cook-in-can' technique allows the product to be shelf-stable for years without preservatives, preserving the fish's natural omega-3 fatty acids and delicate flavor.

Quality control is paramount; each batch is tested for mercury levels (consistently below FDA limits), and the company's 'Trace Your Fish' program allows consumers to track their salmon back to the specific fisherman who caught it.

Denali Furniture Company

"Handcrafted furniture from reclaimed Alaska spruce, birch, and aspen with wilderness-inspired designs."

A Living Tradition

When a massive windstorm toppled thousands of trees across Alaska's Interior in 2003, most people saw disaster.

But furniture maker Tom Hendricks saw opportunity.

His company, Denali Furniture, specializes in creating furniture from wood that would otherwise go to waste—trees felled by storms, logs left behind by beavers, and wood recovered from abandoned logging camps.

Tom learned traditional woodworking from his grandfather, who came to Alaska during the gold rush.

The techniques are old-world: mortise-and-tenon joinery, hand-cut dovetails, and finishes made from natural oils and waxes.

What makes Denali's furniture unique is its integration with the Alaskan landscape.

Coffee tables incorporate river rocks collected from the Nenana River, cabinet doors are made from birch bark, and chair backs are shaped to mimic the curve of a wolf's spine.

Each piece tells a story—of a storm that brought down a spruce, of a beaver that shaped a riverbank, of a craftsman who refused to let beautiful wood go to waste.

The company's motto is simple: 'Every tree deserves a second life.' This philosophy has attracted customers from across the country who appreciate the combination of sustainable practices and heirloom quality.

The Art of Handcrafted Excellence

The woodworking process at Denali begins with careful selection and drying of reclaimed wood.

Each log is assessed for stability, checked for metal (from old fence wire or nails), then milled into lumber using a bandsaw mill that Hendricks built himself.

The wood is stacked in a drying shed with precise air circulation, a process that takes 2-4 years depending on thickness.

Unlike commercial furniture manufacturers who rush the process, Denali lets nature dictate the timeline.

Once properly dried, the wood is planed and prepared for construction.

Every joint is hand-cut using traditional techniques; the mortise-and-tenon joints are so precise that they fit together without glue, relying on the natural expansion and contraction of wood to create a bond stronger than any adhesive.

The finishing process involves applying multiple coats of a mixture of tung oil, beeswax, and carnauba wax, hand-rubbed between coats until the wood achieves a lustrous, water-resistant surface.

The final step is adding the unique Alaskan touches: river stones polished smooth for handles, birch bark inlays, or antler pulls for drawers.

Each piece is inspected by Hendricks himself, ensuring that it meets his exacting standards for both craftsmanship and environmental responsibility.